How to survive as an Artist (a manual)

Junge Künstler*innen müssen Überlebensstrategien entwickeln. Dazu gehören neben der passenden Wohnform die Bereitstellung von finanziellen Ressourcen und die Arbeitssicherheit. Im Studiengang Contemporary Arts Practice haben sich HKB Studierende Gedanken gemacht über Ressourcen und Herausforderungen. Die HKB-Zeitung publiziert die Ideen und Skizzen der neun CAP-Studierenden.

Dr. Lukas Bärfuss, Dozent am Y Institut der HKB und Autor, schreibt zur Aufgabe, die er den Studierenden gestellt hat: Kunst ist kein Sprint, sie gleicht eher einem Langstreckenlauf. Künstlerische Projekte brauchen Zeit, die Entwicklung der eigenen Sprache braucht Zeit. Wer sich einen künstlerischen Beruf gewählt hat, tut gut daran, die Ausdauer im Blick zu behalten. Nachhaltigkeit und Resilienz, gesunde Beziehungen, Arbeitssicherheit, stabile Strukturen, ausreichende Ressourcen, die Finanzen, der Aufbau eines intakten Ökosystems – das sind notwendige Voraussetzungen, damit einem unterwegs die Puste nicht ausgeht. Manches können wir beeinflussen, anderes müssen wir hinnehmen – es ist entscheidend, das eine vom anderen zu unterscheiden.In unserem Kurs «Der lange Atem» im Masterstudiengang Contemporary Arts Practice betrachteten wir in diesem Frühjahrssemester die weichen, psychologischen Faktoren wie Motivation, den Umgang mit Rückschlägen und die Bewältigung eines Erfolgs. Die Öffentlichkeit urteilt, künstlerische Menschen müssen mit Kritik rechnen. Daneben studierten wir die harten Faktoren: Wie schaffe ich mir eine nachhaltige, wirtschaftliche Grundlage? Wie finanziere ich meine Projekte? Was gehört in einen Vertrag, und wie verhandle ich ihn? Denn jede Ressource ist begrenzt, und ob man es selbst erstellt oder nicht: ein Budget gibt es immer. Bei dieser Aufgabe schrieben die Studierenden in genau 58 Minuten genau 2958 Zeichen zum Thema «How to Survive as an Artist» – ein klarer Rahmen hilft der Kreativität auf die Sprünge.

The Art of Hygiene and Sartorial Expression

By Tania Al Farouki

Survival of the fittest starts with looking after yourself. How does that relate to who you are as an artist? Plenty. To put it simply, it mostly has to do with who you are as a human. Practically speaking, looking after yourself mirrors self-respect, and thus a respect for the environment you are in, which is usually filled with individuals. Peers or random folks. Maintaining cleanliness and hygiene is vital and required. At no extra cost. There is one key ingredient here, and it’s mainly wrapped in one word: effort. Making the effort, prioritizing this self-care philosophy ultimately contributes to the collective well-being. We’re not saying don’t get your hands dirty – on the contrary. You’re an artist. You build, you destroy, you try, you fail, but you’re always there, making a mark, attempting to make an imprint, attempting to connect and create a dialogue of some sort. But, make sure to wash when you’re done! There have been countless studies demonstrating the benefits of maintaining a level of hygiene, including the improvement of general wellness, mental health, self-esteem, and the creation of a more wholesome environment… Adopting such habits should be a joy, not a burden. Which leads us to the next step: getting dressed. Here, you should seize the opportunity to take a mundane activity and transform it into a collective effort on a whole other level: maximize your sartorial expression. This additional effort can mean many things for many artists. We don’t expect you to be over the top and plan every outfit meticulously, but to be you. Whether you agree or not, how you look and how you present yourself to the world says a lot about you, especially in today’s day and age. It goes without saying that we’ve passed the days of labels – you need to be a savvy shopper and consume consciously. Less is always more. And more importantly, you “make” the dress, the dress does not “make” you! How many times have we seen ensembles overpower the one who’s wearing them? Attitude is key, here, and the point is owning oneself and nurturing your identity while embracing every sartorial layer. We should see grooming, self-care, getting dressed as an art form on its own. On the long run, it becomes effortless and can easily be transformed into yet another outlet of creative freedom. Your argument will now probably be, “well maybe I wish to defy these societal norms and impositions; I wish to opt for the opposite and make a statement”. Our take is that you should aim to take drastic measures without compromising your well-being. We know that as artists, we take our passions to such colossal proportions that we become instantly vulnerable and will stop at nothing to get our message across. Being “clean”, and “fresh” can be very powerful – you owe it to your very existence and those who surround you. All these elements lead to fostering the artistic communities, and make it grow. You might not see it right away, but you will. Some day…

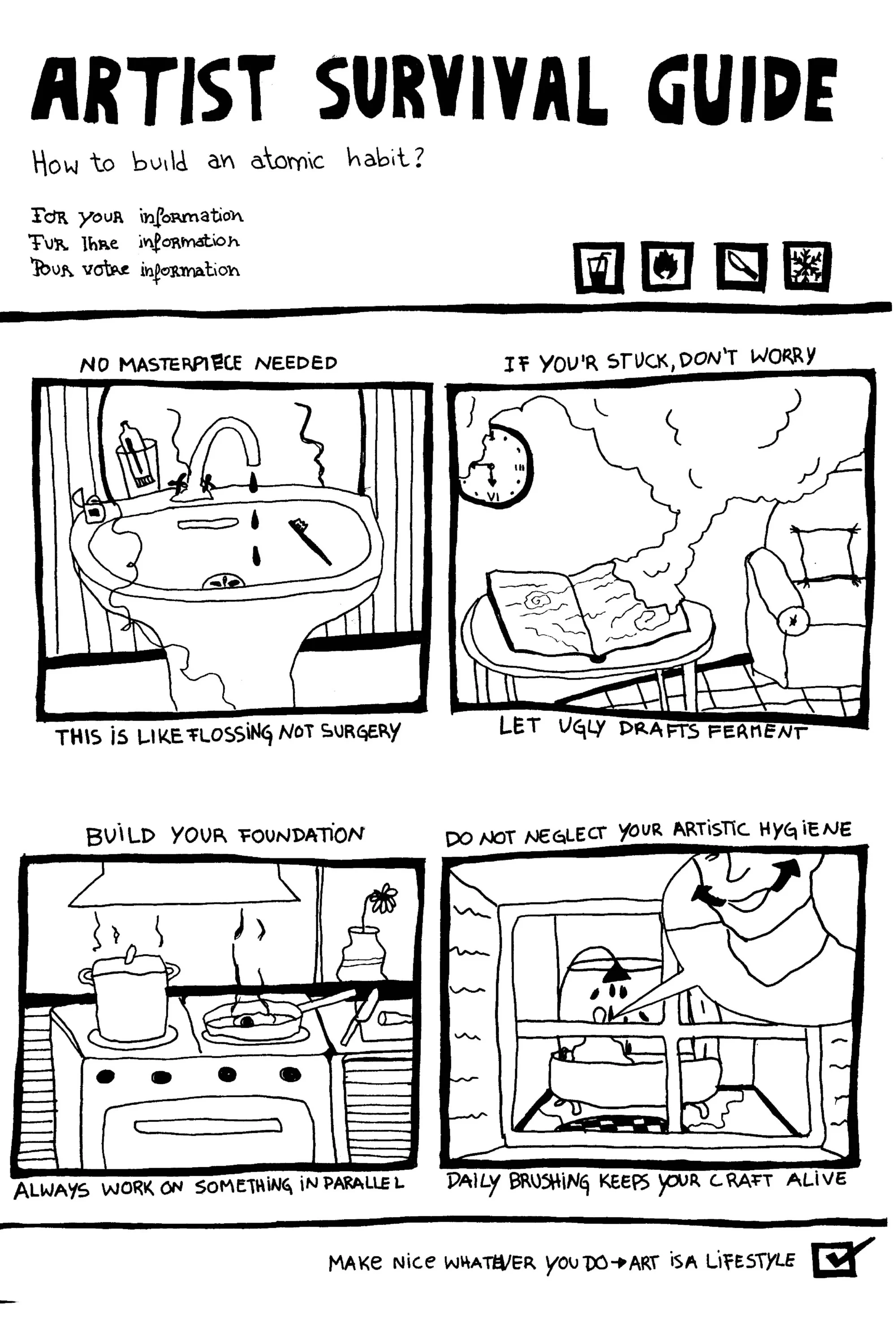

Habits

By Anastácia Kazmina

People often don’t realize that small habits and everyday choices are already shaping who we are. The four stages of habit formation are: noticing, wanting, doing, and liking.Many think they need motivation, but what they really need is clarity. When you wake up, you might not feel like doing something and the key is knowing what, when, and how, just like brushing your teeth. We’ve all been there before: You try to build a habit and then you fail. Ask yourself: Why did I fail? Think about the challenges you had to face. Once you see those obstacles clearly, you can plan how to avoid the disaster.Change your environment, make it obvious and put what you want to do right in front of you. Make it easy, just start. After you start, focus on the starting line, not the finishing line. Don’t worry about the results, they’ll come naturally. We repeat behaviours because we enjoy them.Your brain tricks you into thinking the reward only comes at the end, but you need to feel rewarded while doing the action. Stick to a routine, even on bad days. Just showing up builds confidence, and your actions prove who you are or who you want to become.

Rhythm and Discipline

By Benjamin Kevera

The people, the projects, the pastimes, the objects – but especially the people – I love most in life, anything that I love for more than an initial romance, I will hate on some days. Take my brother for example, whom I love and whom I would die for, but on some days his stubbornness annoys me so badly I just want to smack him. Having been married to one big project for half a decade now, having loved it very much for a long time, having seen it grow and starting to feel, it will always have a special place in my heart, even after the deadline. Even with all the love and work I put into it, on some mornings I will be laughing at it when it tries to walk, I will blame it for having wasted some of the best years of my life on it, I will be ashamed of being seen in public with it. And that’s OK. Because the next day – if it’s a writing day – I will get out of bed on the same beat, I will have the same cup of PG Tips original blend black tea, eat more or less the same breakfast, enjoy the sunlight shining in or watching the sunrise if it’s winter and then sit at my desk and think about happiness and bitterness beyond the next great bottleneck for two to three hours before it’s time to start cooking lunch. Some days there’s just more happiness involved in doing that. But it doesn’t really, really matter if it was great today. If it was great, that’s lovely of course. If me and my partner mess up this figure, if I step on her foot, or if she misses a beat, we’ll always be able to skip one and restart on the next one. When thinking about rhythm on a surface level, there isn’t much of a science to it. On 1, show up. If you feel great, do all the pirouettes, spins and jumps you want. If you don’t feel it right now – just clap. For me personally, a lot has changed, not only in writing, but also in health and life, when I started to allow myself to feel negatively about the things I like. When I didn’t judge my self-pity. The anger and frustration. Hating myself for being unable to produce a single usable sentence in an entire day of work. Trying to supress and judge that led me to a lot of, dunno, not nice stuff. But for as long as the beat goes on, there is a new moment for beauty, a fresh potential for greatness, the chance of falling in love with the same old friend again. The probability of life itself having started by complete coincidence is soooooo ridiculously tiny. But on an endless timeline, given there have been many gazillions of possible moments for it to happen, is it really surprising, that life did eventually happen by chance.In that sense, all that has to be done is to show up on the next beat, and repeat and repeat.And on some days, I clap only once.

Funding, Foundations, Grants, and Ethical Questions

By Jonas Sollberger

How can you find grants for your project that fund not only materials but, more importantly, your own essential living expenses? Switzerland is a wealthy country with a lot of money. Finding that money, however, is another question – because it’s often hidden. Here is what we can consider one of the main reference, the official website of the Swiss government called “Stiftungsverzeichnis”: esa.admin.chThis website lists all foundations. There you can select your field and find many (but not all) existing foundations and grant opportunities in Switzerland. Make a solid application These institutions don’t just throw money out of the window. Getting a grant means becoming a specialist in preparing 14 copies of your application, with cover letters, estimates, CVs, and a pinch of desperation. All of this, of course, with no guarantee. And while some people turn into full-time bureaucrats, others prefer to simply get a job, save money and preserve their creative energy. Foundations often only consider applications if the artist has already published a work or held an exhibition. There are many ways to find funding. However, it’s important to always consider where the money comes from and how it aligns with your values and public image. Sometimes, certain sources of funding can harm your work rather than help it, depending on their origin. Keep in mind that a foundation will often make public the individuals or projects it supports and may expect to be acknowledged in publications or when awards are received. Think carefully before applying for or accepting money that could be considered “dirty”, such as that which might come from a bank that would suddenly decide to support the arts for reputational purposes. Another option is to approach your own municipality. The city of Zurich is known as a kind of promised land: There’s supposedly so much money there that some people seriously consider moving. But here too, from a personal standpoint, I want to bring back the ethical question. For example, knowing that the municipality is cutting and reducing social aid as much as possible – is it ethical, as an artist, to be awarded a generous sum by the city for your project, while that same city abandons marginalized people to distress and subjects them to morally questionable reintegration programmes through psychological pressure? You have to find what works for you – experiment, try, be clever. But let’s keep our eyes open: Behind the word “grant” there is always an agenda, a power dynamic, a compromise. It’s up to each of us to decide how many pieces of our soul we are willing to mortgage for funding.

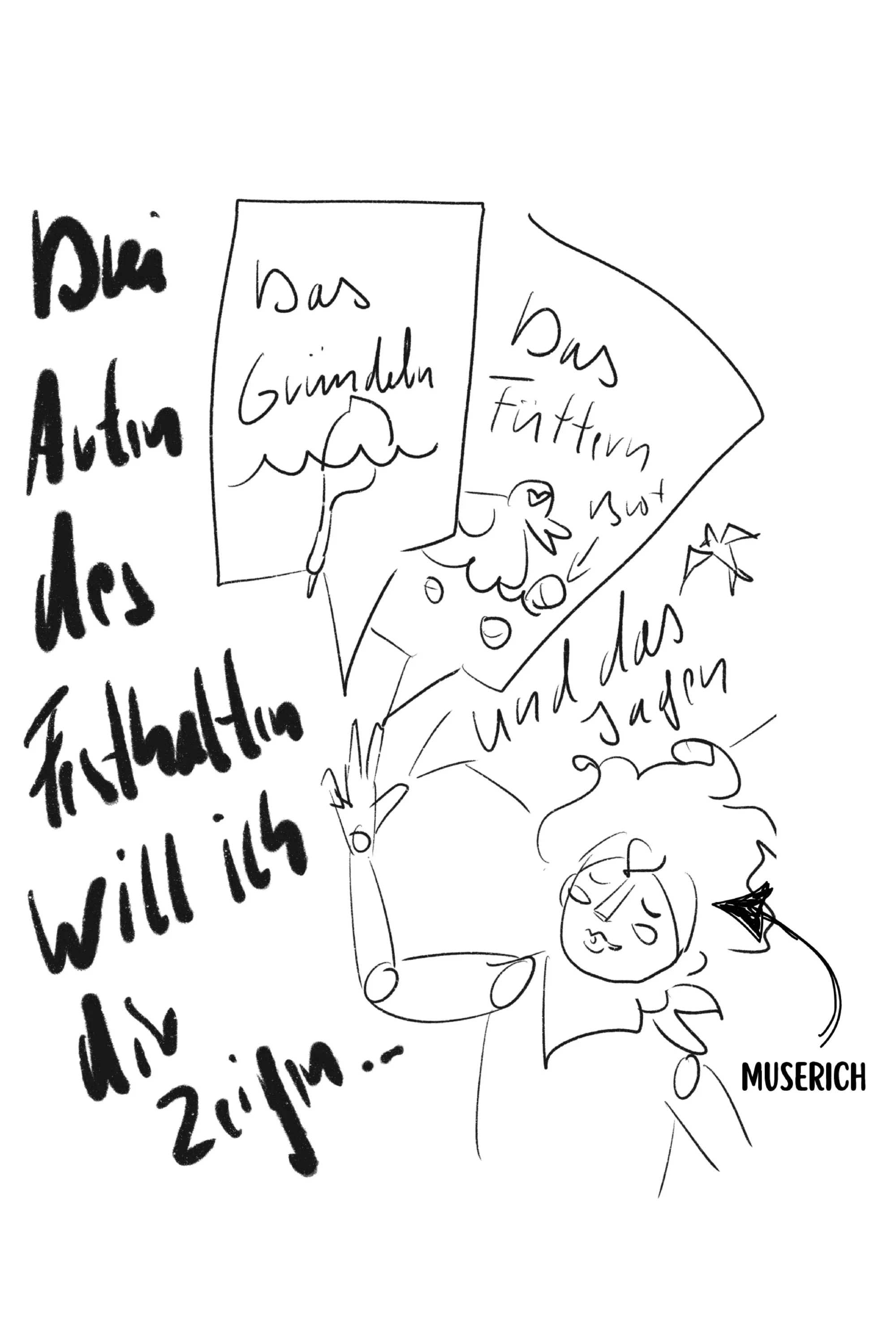

Sketch the Catch & Hatch the Sketch

By Joanna-Yulia Kluge

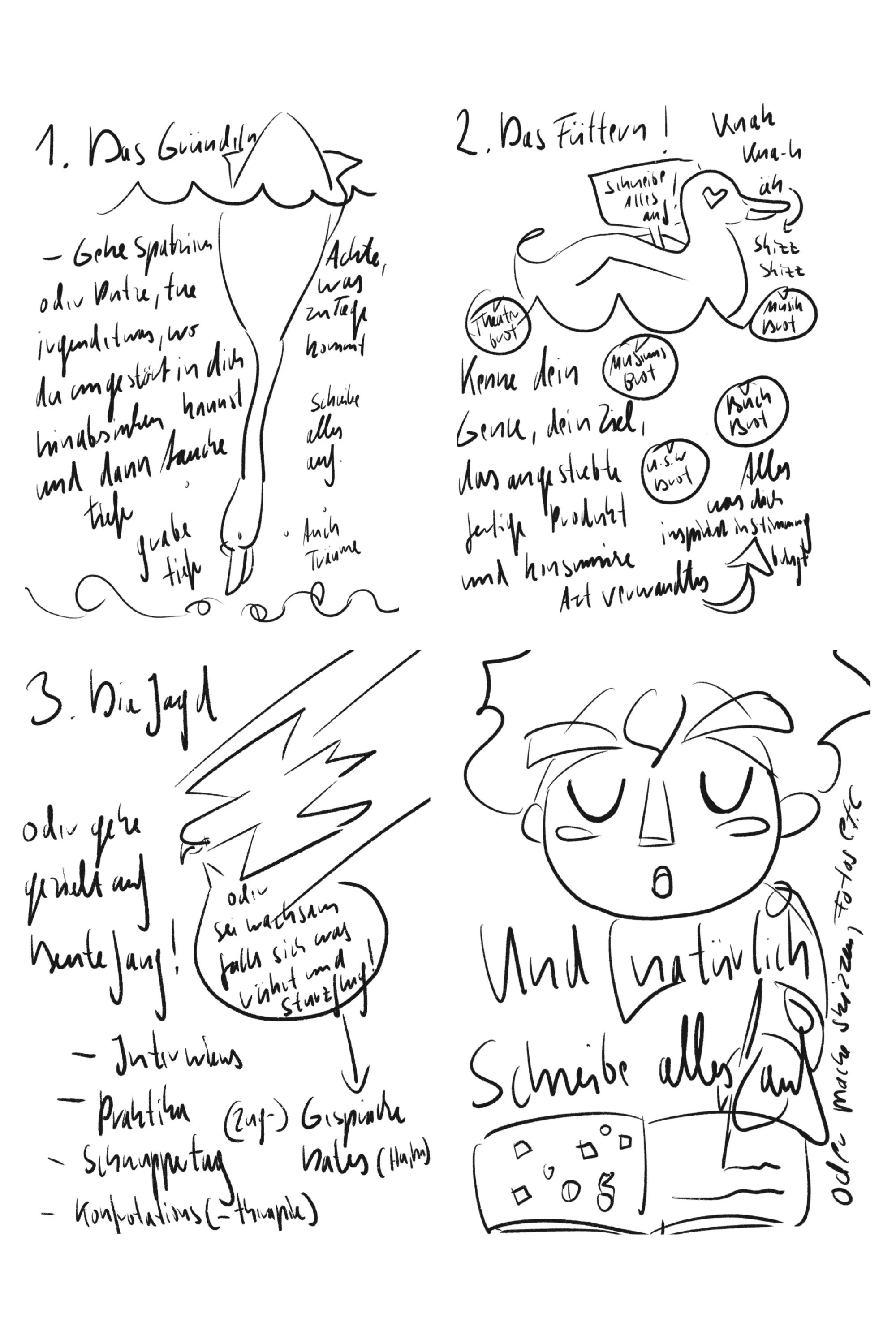

I will show you three ways of sketching: rooting, feeding, and hunting.

1. The Rooting: And now: go for a walk or do the dishes – anything repetitive that lets you sink deep into yourself. Listen inward. Stay open – write everything down. Even dreams.

2. The Feeding: Know your genre – what are you aiming for? What is your goal? Consume similar works: go to the cinema, listen to music that puts you in a similar mood or era, read (non-)fiction, anything that inspires you further – and stuff yourself with it. Mix it all weil in your stomach – yummy? 😉

3. The Hunt: Go on a targeted hunt – through interviews, trial jobs and/or instead of, internships. Always be ready to pounce when you spot something: conversations on trains, people’s looks, sounds, smells – catch it all!

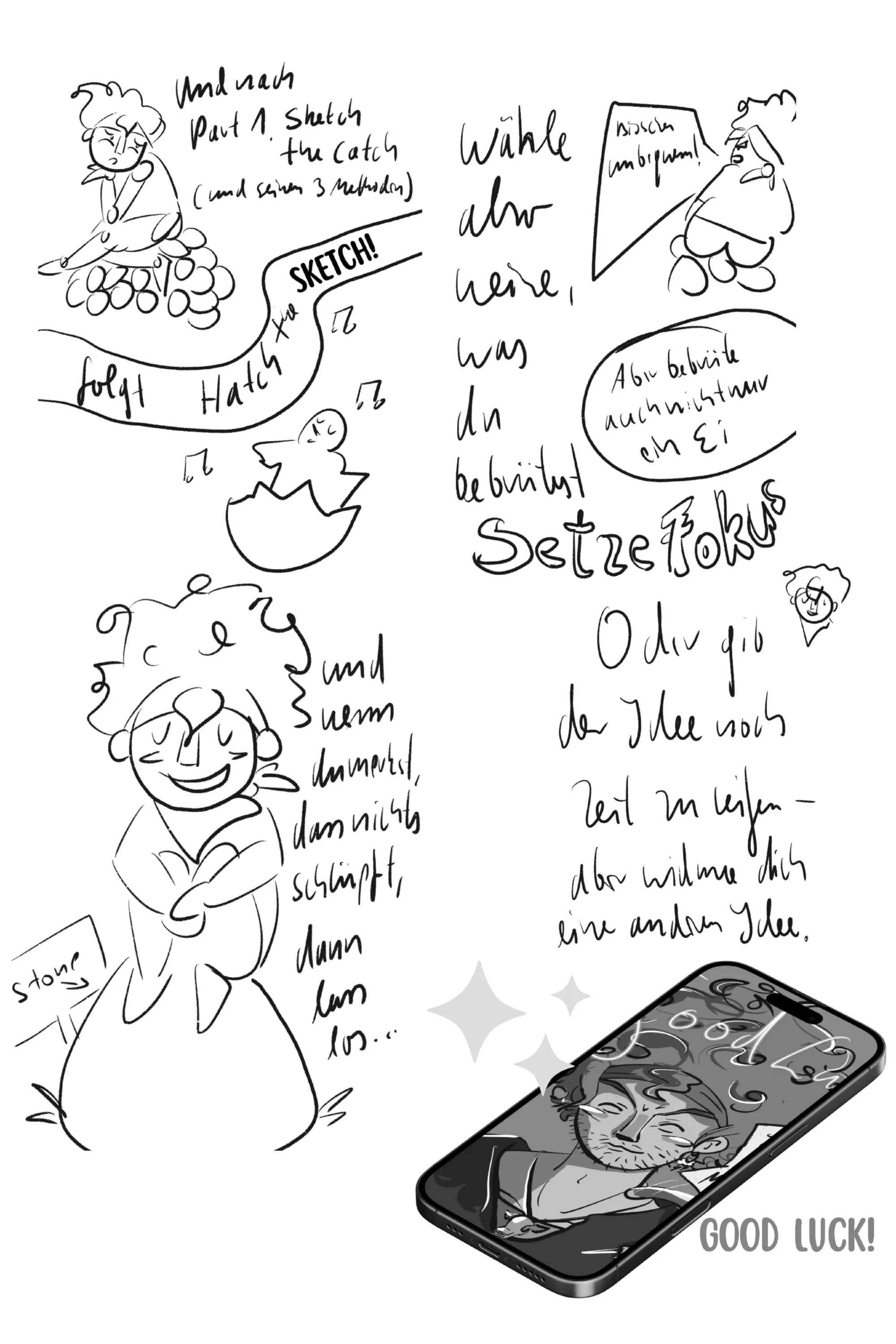

And once again: ALWAYS write everything down or record voice memos, take photos, make sketches. Always carry a sketchbook with you.And after Part 1 Sketch the Catch with the three following methods: HATCH THE SKETCHChoose carefully what you decide to hatch.

Focus – but don’t put all your energy into just one egg.And if you notice that nothing is hatching, then let go. (or give the idea a little more time to ripen), but turn your attention to another idea.

Frames

By Fabian Oderbolz

One good thing is that we can think about thinking.We can mediate the way we think by changing the mental instruments we use to think or by shifting the grounds on which we stand to do that thinking. The frame from which we operate colours the outcome of our thoughts and actions. A frame is a lot like a set of assumptions about the world.A frame is a tool. A frame is like a pair of glasses.Different glasses let us see different things, differences in emphasis, differences in resolution, differences in scale. If I look at something with my red pair of glasses, I may see a problem. If I take the red pair off and replace them with my green pair, I may no longer see a problem, but instead find an opportunity. Or I might find many new problems and questions. Likewise, a shift in frame may make an issue disappear altogether.A frame is also like a stool. A stool is a question of height. It is a question of the distance from the ground. I can stand on a stool that is tall, I can stand on a stool at regular height, or I can stand on a tiny stool close to the ground. What I see changes depending on the stool. What I can reach on the shelf changes depending on my distance from the ground. Things that previously seemed out of grasp may become considerably more likely if I simply stand on a different stool.Frames can help us consider alternative realities, other possibilities or enter new realms altogether. They can help us come up with new sets of questions.Becoming conscious of the frames we operate with is an important skill to cultivate as an artist.Frames are no small thing. They may help us survive as artists. They are part of our toolbox. Frames help us make decisions. They help us act, they help us sort things through and differentiate. Frames may even offer a sort of stability or certainty when uncertainty is otherwise the basis.Examples of useful frames are:I’m practising.The universe is plentiful.Capitalism is on your side.It’s important to be stubborn.Ambitions are images that help you reach for something.You are giving. Your profession is giving. A particularly important frame is a deceptively simple one. Maybe it is the most basic frame for our line of work. It goes like this: I am an artist. This is an assertion with consequences. It entails that whatever you do, you stay an artist. Whatever you do, you do it as an artist. Being an artist does not begin when you enter your studio, sit down at your desk or step on stage. And being an artist does not end when you put down your pen, wash out your brush or stop singing. You stay in the work. You remain in your art whenever, wherever. Being an artist is no longer conditional. It means that if you are willing to work, you will. You interact with the world as an artist, and you teach the world to interact with you as an artist. Habits, routines, discipline and other useful tools in our toolbox rely on this frame.

Community vs Competition

By Maria-Lusie Tzikas

How to survive as an artist? You won’t, because we’re all going to die at some point. Ha, ha. But let’s focus on how we could make the road to death a bit more fun for you. Let’s start with something very simple, but that we forget very often: You’re not alone. It’s true, that only because your friend jumps out of the window, you don’t have to jump necessarily too (Thanks mom, I got it!), but if there is a nice mattress waiting for you outside, it would be a loss not to do it, just because someone else is doing it too. It can be something very freeing to accept that you’re not the only one working with a specific technique, in a specific field or on a specific topic. But to feel this freedom is only possible, if you don’t see them as your competition. So, instead of trying to be oh-so-different (there will be anyway always differences between you and those other artists, you just don’t know / see it yet), why don’t you exchange and engage with those artists? Obviously, it can be very nurturing to exchange with artists that are very different from you too, but there is a big potential in similar artists. Because eventually you will apply for the same foundations, scholar ships, grants, etc. and you might work with people they have been working before with, etc. – so you will be able to benefit from their experience. Who can understand you more than another artist? Especially a “similar” one to you. So ask for help and advice. There’s no shame in it. History has shown that wherever people get together great things can happen (horrible ones too, but you know what I mean!). Together you can fight for better salaries, better treatment, draw attention on open calls and warn each other of collaborations with artists/people that will exploit you. And much more. Also, don’t forget to ask yourself from time to time: Why am I doing what I am doing? Because I want to be the best or because it’s a very important topic for me and I want to raise awareness in the public? Or because I like to express myself in that technique and I want to share it? Or because because because … Usually, the answer is rarely, because you want to be the best in something. Or if that’s really your goal than maybe you should ask yourself if you want to be the best, only because there’s no one else in that specific field … Anyway you turn it, it will never be from benefit for you feeling like you’re constantly fighting against the people that surround you. We’re anyway already fighting institutions which don’t want to pay us sufficiently, people that degrade our profession as an artist, etc. and not having to fight those fights alone will lead to more energy for your art. It’s a very long run, let’s make it an enjoyable one.

The Material

By Jonas Gut

As an artist one might get the feeling that there exists a need of “honouring the material”. Why should one “honour the material”? When is “the material” to be considered as “honoured”? What “material” expects being “honoured”?A helpful guideline or limiting truism?As with so many things it’s both and neither, a mix of the two. There are many instances where honouring the material you work with will yield an authentic and positive result. Let’s say you take a series of interviews and historical documents as the basis of an artistic work. IMHO, this is a perfect instance where “honouring the material” will give your piece an edge as a cultural time capsule or a summary of the human condition. By reflecting the truth within these sources (your material or) you will honour it in a way that seems true with the art piece. Just as one should credit one’s influences in course.However, there are just as many moments where “honouring the material” might impede your artistic expression. Artists are compelled to stick out, subvert the status quo, be at the vanguard of cultural change and revolution, to see things in a different light, make others question their own notions about the world. Art is most alive in sub- and countercultures where rules are broken, the unkempt, organic, anti-, non-commercial thrives. Where known standards get undermined, built upon or disregarded completely.Honouring something might be in the way of innovation and artistic expression. After all we would not have modern music, if the Beatles had not listened to rock’n’roll which was influenced heavily by Elvis, who stole much of his work from people of colour who had no regard for what some people would have called “honouring the material” this material being “decent” music, classical music, white music.Of course not every piece needs to break all of the rules to be worth something but by simply upholding the given set of rules, “the material”, art is not created.Just as art is not created simply by reacting adversely to what is considered the standard of doing something.By following Freytag’s Triangle of rising and falling action a masterpiece is not created and you will not create one if you turn the triangle on it’s head.Know the rules so well, that you know when to subvert them, when to follow them. Meaning, “honour the material” in the right moment and disregard its feeling of being disrespected in their respective right moments. “You shall not make any idols to worship”, applies much more to art than to spirituality. Other artists are just as human as you are. Letters are just letters, paper is just paper, paint is just paint, a canvas, a poem, a wall, a verse, a genre, a classic, a sound, a norm, an instrument is just that. No need to honour something, just because it has existed before your art. Honour only art.

The Creator

By Lija Kramer (Mariia Gimazutdinova)

Do I have the right to create? Who am I, really, to call myself a creator? These questions haunt me and my colleagues all the time. And the more toxic the culture a person comes from, the louder these questions echo in our minds. They interrupt the creative flow and steal our inspiration.I’ve studied and worked with many people who produce content – but I know even more people who’ve devoted their lives to art and never dared to make their own original contribution. I come from a musical background and in music, those who don’t compose but only perform are called executor and not musicians.In Russian, the same word (Исполнитель) also refers to someone who merely follows orders – someone without their own will. And I’m so glad that in English we use the word performer, which implies freedom of expression.I’ve always been curious: At what point do people get this ridiculous idea that only a select few have the right to create, while the rest must remain mere shadows, too shy to dare call themselves artists?Think back to when you were a child! You weren’t afraid to fail. You jumped into cold muddy puddles, played with clay, made up stories, drew treasure maps and composed songs.Each of us is born with a divine source of creativity and individuality, and its capacity is truly limitless. We do not have the right to trade our gift for doubt and hesitation.There’s nothing worse than waking up at seventy and realizing you spent your whole life hiding your creative nature, fighting yourself – ending up as a fruitless seed that never grew.To me, creativity is a metaphor for life itself – we are built to produce results, to invent, to achieve success, to compete and win, to imagine and to decide. These are the traits of a healthy, competitive human being – instilled in us by nature itself. It’s thanks to our spirit of innovation and boldness that we’ve survived this long and made it to 2025.I love talking to people. Six months ago, before moving to Switzerland, I worked as a mentor for creatives. In that role, I often talked to conservatory teachers, my mom’s musician friends (she’s a teacher too)and my own colleagues.Too often I heard regret in their voices as they told me how in their youth they were creatively active – but then they stopped.“I used to write pieces like Tchaikovsky.”“Why did you stop composing?”“Oh, I could never be like Tchaikovsky!” (laughs)Of course she won’t be like Tchaikovsky – because she doesn’t live in the 19th century, because she had different teachers, a different musical context – and simply because she’s not Tchaikovsky.And yet, this obvious, uncontrollable fact was enough to dramatically and seriously shut down her desire to compose.Let’s never do that to ourselves.Dostoevsky wrote in Crime and Punishment: “Am I a trembling creature, or do I have the right?” It’s a bit of an extreme analogy, because in his novel this question leads the protagonist to commit a murder (very Russian, yes I know) to find out whether he’s a victim of his actions or he has the right to chose what’s right and what’s wrong. I would say it loudly now, print it as a poster on the wall, and make everyone a T-shirt (HKB, please give me a budget!): YOU HAVE THE RIGHT TO CREATE!You don’t need to be a genius – because no one actually knows what a genius is.You don’t need to be perfect – because no one knows what perfect is.And guess what? You don’t even need to be good at creating – because yes, you guessed it – no one knows what makes a good creator.Let’s pretend you’re a genius, okay? Just for a little while … like 50 years.And please develop fortitude in yourself, remember that opinions about your work will always be there, and very different. If you have created something, do not doubt: You have wrinkled the matter of the universe a little, enriched the information space, laid the foundation for a new sprout. You are a little bit of a god. Do not lose your amazing spark, because it illuminates life with meaning!I love you, as a creator loves a creator.